Photo by Centre for Ageing Better on Unsplash

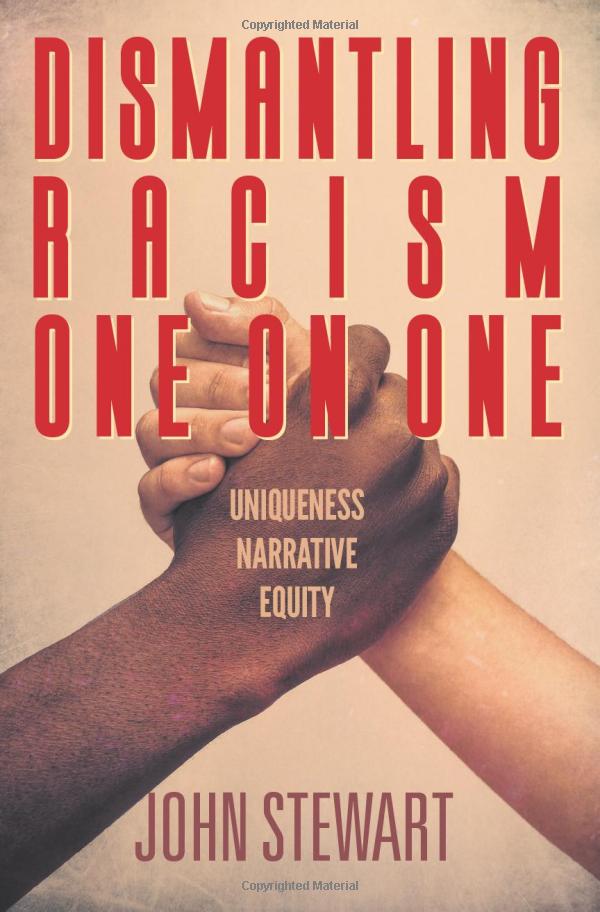

My new book, Dismantling Racism One On One highlights the power of each person’s uniqueness to transform racist interactions. The key, as I explain there, is for conversation partners to co-construct uniquenesses. I re-tell three true stories of racist interactions where conversation partners did this, and I describe how every reader can help this happen by offering and inviting some combination of a reflection, a choice, or an important feeling (Chapters 6, 7, and 8).

In the May 16 New York Times, therapist Dr. Orna Guralnik describes what she has observed in her work with struggling couples, and her insights overlap and reinforce what Dismantling Racism One On One says. She writes,

One of the most difficult challenges for couples is getting them to see beyond their own entrenched perspectives, to acknowledge a partner’s radical otherness and appreciate difference and sovereignty. People talk a good game about their efforts, but it’s quite a difficult psychological task. To be truly open to your partner’s experience, you must relinquish your conviction in the righteousness of your own position; this requires humility and the courage to tolerate uncertainty. Coming to see the working of implicit biases on us, grasping that our views are contingent on, let’s say, our gender, class background or skin color, is a humbling lesson. It pushes us beyond assuming sameness, opening up the possibility of seeing our partner’s point of view.

I call it “uniqueness” and Dr. Guralnik calls it “radical otherness.” We both emphasize the importance of courage and humility. She emphasizes the usefulness of lessons learned from both the #Me Too movement and Diversity-Equity-Inclusion-Belonging resources. These lessons clarify challenges posed by implicit bias, white privilege and fragility, allyship, and systemic racism. One white male who is married to a person of color explained what he’d learned this way: “Everything about me was raised to believe I am not racist or privileged, but in recent years I realize how easy certain things have always been for me simply because I’m white. I am humbled. And that has changed the way Rebecca and I talk with each other.”

As a psychoanalyst, Dr. Guralnik helps couples reflect on and reframe understandings and beliefs they’ve developed that make it difficult for them to relate to their partners in healthy ways. This is important work. Those without access to psychoanalytic guidance can also mobilize the power of uniqueness–or “radical otherness”–by following the suggestions in Dismantling Racism One On One. The storiers there illustrate how three racially mixed sets of conversation partners dismantled the racism that was happening between them by co-constructing theirs and their partner’s uniquenesses. The close readings of their conversations make clear specifically how they did this. Then three skill building chapters show how you can do the same thing–transform the racist conversations you’re in. The final chapter recounts a racist conversation where this didn’t happen, so the book as a whole offers both helpful understandings and useful behaviors.

As Dr. Guralnik points out, several broader cultural changes support the efforts of people who want to do this work to reduce the toxic polarization that threatens democratic governing and general civility. One of these changes is from repressing uncomfortable parts of our country’s history, such as the Doctrine of Discovery, boarding schools for indigenous children, the Tulsa massacre, lynching, and racism in the G.I. Bill to teaching full accounts of both of the country’s two “orioginal sins.” Another is from the glib conviction that, since just about everybody has to work hard to succeed, there is no such thing as “white privilege” and “all lives matter” to the acknowledgement that indigenous and Black lives have too often not mattered in the past, so we need to emphasize how they do matter now. And another is from the vague realization that social stereotyping is bad to a grasp of what to do instead–co-construct uniquenesses.