Well before Starbucks, coffee came in metal cans that opened with a key. You pried up the tab at the top of the can, inserted it into the slot on the key, gave a sharp twist to pop the vacuum seal, and enjoyed a delightful whiff of fresh grounds. Then you kept winding, until the sharp metal spiral around the key had to be disposed of gingerly, and the lid was left with a similarly-sharp edge. This was why most families kept coffee in a canister—and why Folgers and Hills Brothers soon turned to rim-free tops.

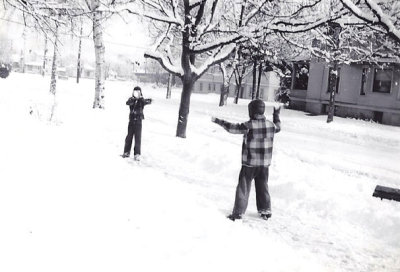

But before these improvements, my boyhood buddy “Worm” and I (his real name was Norman), discovered that, if we hammered down the edge, the metal disks would sail almost as far as the plastic “Flyin’ Saucers” that Woolworth sold for a dollar. Those didn’t become the famous Frisbees until about 1957. But in the early 1950’s, our home-made disks easily sailed the full length of the gravel church parking lot that was our playground on week-days after school. We even found that, with practice, you could make the lids curve and sometimes land where you aimed.

The major downside of this diversion was that, even after careful pounding, the edge of the disk was still sharp enough to be painful to catch. And one day, in the midst of a combat game, Worm’s feisty toss and my slow duck left a shallow gash in my forehead—not deep enough to require stitches, but bloody enough to prompt mom to confiscate our stash of hammered lids.

Generations and Their Games

Some young people probably ask their parents or grandparents, “What was it like when you were growing up?” But usually the question surfaces more subtly, accompanied by emotional overtones varying from genuine interest to disbelief or pity. Our four and five year old grandsons show little interest in the coloring, drawing, board, or card games that we enjoyed as kids. Left to themselves with bikes or balls and room outdoors, these young ones complain that they’re bored and beg for their iPads. Our older grandkids’ puzzlement at our enjoyment of a the Sunday newspaper implies, “Why juggle paper pages when you have the Huffington Post online?” And when my 20 year old shows me how me to take a selfie with my smart phone, his look says, “Didn’t they have anything like this when you were growing up?” Young ones can’t believe how we filled our days before there were screens.

If and when I’m asked this question, I reply, if they want to listen, that part of what made the 1950’s entertaining was that the culture gave us, not screens, but story-lines that were easily elaborated into full-on past-times. For example, it’s hard to imagine in these days after 9-11, but in the aftermath of the great victories of World War II, combat was glamorous and exciting. Abundant reports in the Daily Chronicle and the newsreels at the Fox Theater celebrated V-E and V-J days—and later, the successes of the Korean conflict. These made war games one of our favorite activities. Plus the gravel at the church made it easy to shift from disks to rocks. Of course, the rocks we didn’t dodge made marks too, but most of these lumps or bruises were easier to hide than the gash from the coffee can lid.

When we tired of assaulting each other, or the church lot was full of cars, we had other options. Just up the block from my house, a dense hedge that separated the corner Shell station from the adjacent boarding house provided room and cover for a seasonal fort. With a small hatchet, Worm and I hacked off enough inner branches to create standing room, and the stubs of the limbs became hangers for our necessary equipment, most of which came from Yard Birds, the local army surplus store. The quilt-jacketed canteen kept Kool-Aid tepid and tin-tasting, an olive drab flashlight permitted after-dark operations, cheap opera glasses served as binoculars for spying on my sister and her friends, and there was always a stock of home-made slingshots, which could do real damage

In fact, we seldom fooled around with pretend rifles, pistols, or machine guns. Trees and bushes made it easy to construct weapons that worked almost as well as store-bought. Vine maples offered plenty of forked sticks that could be slotted near the tips of the forks, fitted with rubber strips cut from old inner tubes we liberated from the Shell station’s garbage can, and finished with a pouch of leather cut from a scrap found in another favorite scrounging spot, the cans behind Churchill’s, the local glove factory. Rocks were standard slingshot ammo, but ball bearings worked even better.

Aggressive archery was another option. Comic books, radio shows, and movies featured western stories, and there was nothing politically incorrect about playing cowboys and Indians. Books from the Carnegie Library told us that Apache and Comanche warriors carved yew wood into bows. So, with a couple of other friends, Worm and I scouted Seminary Hill like amateur arborists until we located what we thought was a yew, where we cut four-foot limbs to carve, bend, and string. The supply tree turned out to be a cedar, which meant the bows stiffened as they dried, but while they were green, they worked just fine. Since the books said arrow-making required splitting, carving, and fletching shafts from chunks of cedar trunks, we decided to invest our meager weekly allowances in the cheapest ones the sporting goods store carried.

You can guess where this led, but without the benefit of hindsight, we couldn’t. It was a triumph when one of my arrows actually sailed over the top of the flag pole in the City Park. At least it looked like it went over, from where we were standing. But the first time my arrow fatally pierced a robin soured me on the sport forever. And Worm managed to get our slingshot collection confiscated and burned when he put a ball bearing through Pastor Lucas’ garage window. We still played war games, but our tiger was pretty toothless.

China creek provided another set of almost endless diversions. It was a stream that still runs right through the middle of our small town, connecting the sawmill by the railroad tracks on the East with the river at the Western edge. After heavy rains, China Creek was full enough to flow dangerously, but throughout the summer, you could wade in tennis shoes and, even if you stumbled and fell, you’d dry off before it was time to head home for dinner.

The dark places where the creek ran under large buildings were most interesting. Owners often installed fences to keep out kids and animals, but these were rarely effective. The damp coolness was especially welcome on hot summer days, and when you were under the biggest buildings, you knew that nobody would ever find you. Small boys love secrets, especially when small girls won’t go anywhere near them, and we made the most of these hideouts. Occasionally, we even spotted a hungry rat or a wayward bottom fish looking for a place to spawn.

We also enjoyed the water-skippers, periwinkles, and crawdads that populated the Creek. Sometimes “enjoyed” meant rock-bombing them, sometimes we were into collecting, and sometimes the main point was to use them to get girls to scream. But they were another rich resource for fun.

Except for Buck Rogers, our boyhood media heroes moved at old-fashioned speed, which we could at least mimic on bikes. Two-wheelers gave us freedom, of course, and after we turned 12, they qualified us for an actual job delivering the afternoon daily. But before then, we used bikes to explore all the side streets—except the steepest ones—race between almost any two points we could identify, and jump.

I enjoyed the jumping most. My bike was a fat-tire Schwinn-World with patented knee-action. This meant that the front fork was fastened to a heavy spring that acted as a shock absorber. Rough roads were smoothed, but much more importantly, I could land easier off a jump than my friends with stiff Raleigh and Monarch two-wheelers.

Barn boards were almost wide enough for the jump platform, but when plywood came to town, jumps got even better. We’d spend hours laboring with a dull hand-saw—our dads never let us use the sharp ones—to cut a piece wide enough to hit easily at high speed and long enough to really get some lift. Used bricks would sometimes work as props for the plywood, but if they were lumpy with old mortar or cracked, they tended to collapse, which, when it happened, was disastrous. A piece or two of railroad tie was infinitely better, when we could find one and manage to saw it to the right length. The jump had to be set up on the sidewalk to avoid colliding with an unsuspecting car, and that limited the run-up and run-off to a city block. But if you built it with a good slope, braced it in the middle, placed it right, pedaled your hardest, and yanked up the handlebars at just the right time, you could clear eight or ten feet. The top trick was to end by locking your coaster brake and spinning a donut in the lawn or the gravel of the alley. Helmets hadn’t been invented yet.

For at least three summers, the primary project was building and riding a “soap box racer.” Our versions were a far cry from the sleek constructions that competed for a national title. We started with a two-by-twelve about six feet long or a similarly-sized piece of reinforced plywood. Perpendicular two-by-fours almost as long as the car supported the axels, and gave the vehicle considerable stability. The front two-by had to be drilled for a single bolt, so it could be steered. A wooden produce box from dad’s grocery store formed the cowling and provided a place to anchor the steering mechanism. It was made from a section of broomstick, several feet of clothesline, a couple of small pulleys, and a steering wheel scrounged from the local wrecking yard. When the dowel was mounted right, the wheel secured, the rope wound correctly around the dowel, and the ends of the rope led through the pulleys and fastened near the end of the front two-by-four, you had sophisticated steering.

We had to rely on the local machine shop for steel rods long enough to protrude beyond the ends of the two by fours and drilled for a washer and cotter key to keep the wheels from falling off. Rusted Radio Flyers provided the wheels, and we relied on tennis shoe bottoms for brakes. Sometimes we painted these creations, but most of the time we eagerly rushed from construction to use—slathering oil or grease on the axels so we could careen at twenty or thirty miles an hour down Seminary Hill, more than occasionally dodging surprised drivers.

It took a spectacular opportunity to tear us away from the soap box racers, and the summer of 1953 provided one in the form of access to a piece of official equipment owned by my buddy David’s dad. Mr. Hall was a local police officer, and his department-issued weapon was a .38 caliber six-shooter. Without us even asking, he inquired if we wanted to fire it. We were just out of town at David’s grandparents’ place on the Skookumchuck river. If our shorts hadn’t already been soaked from playing in the river, we might have wet them in anticipation and excitement.

Officer Hall gave us some rudimentary instructions and directed us to aim for a branch on the far shore. This was before the two-handed grip you see on TV had been invented, so the weapon wavered unsteadily at the end of our pre-adolescent arms. When I pulled the trigger, the report was plenty loud, but the kick was what really surprised me. I was shocked enough that I stopped after only one shot. David emptied the magazine. My dad had never allowed guns in the house, and maybe his wariness was in my genes. All I know is, it was dang exciting, and that’s the only time I’ve ever fired a pistol.

The main summer activity that got repeated endlessly over at least half a dozen years was the daily visit to the community swimming pool. It was standard for the time—10 x 25—either meters or yards; I’m not sure which, with three-foot and 10-foot diving boards, just over 3 feet deep at the shallow end and 11 ½ feet at the drains. Memorial Day to Labor Day, as soon as it opened until its 9PM closing, the pool bike racks were filled, the dressing rooms cluttered with forgotten goggles and fins, and the baskets that served as lockers crammed with shorts, t-shirts, and sneakers. Flip-flops—at the time, we called them “thongs”—were invented later. Mornings were reserved for lessons that went from beginner through Senior Lifesaving—with the high school kids taking Water Safety Instructor in between.

I relished all of it. After going through most of the lessons, I was there from noon until five almost every day, and now I sport (thankfully minor) carcinomas because of the amount of sun I got. We learned to play water tag in ways that didn’t catch the eyes and prompt warnings from the lifeguards. We did jackknifes, swan dives, and flips from the one meter board, and some—not me—managed one-and-a-half dives off the high board.

Cannonballs were the main competition, and we devised various ways to measure the height of the splash, comparing butt-first tucks, head-first ones, and one-legged efforts we called “can openers.” Nobody I know ever managed to send water as high as the frame of the high dive, but I got it over the lifeguard chair more than once—as I learned from the damp lifeguard’s whistle and scowl.

One evening eight of us were doing chain-cannonballs off the high dive, one after the other in what was supposed to be a fan pattern. A football player from the neighboring town miscalculated, and hit the water right where I was coming up. His chin hit my head, he went to the bottom, I looked up stunned to see the lifeguard diving off the chair to retrieve him, and then I was startled to find blood in the water around my face. It was mine, and I knew I’d been whacked pretty well when I couldn’t remember my basket number as one of the guards took me to the nearby hospital. Eight stitches closed the wound, and my scalp still has a ridge in it. Mom and Dad were pretty shaken, but I thought it was kind of cool that the football player had gone to the bottom while the skinny nerd just bled in the pool. The head bandage made it look worse than it was, and I couldn’t wait to get rid of it so I could get back in the water.

When my buddies and I got past the scatological humor age to the point where we knew the difference between a dirty joke and a clean one, pairs of us used to find reasons to visit the local shoe-shine shop run by Nick the Greek. Nick was a bona-fide local character. The Chronicle even ran a story on him when he retired. He’d emigrated from Greece and regularly sent money back to family members. When I left town for college, Nick told me he’d put four of his nephews through school in Greece. But growing up we were interested in his shop for other reasons.

When my buddies and I got past the scatological humor age to the point where we knew the difference between a dirty joke and a clean one, pairs of us used to find reasons to visit the local shoe-shine shop run by Nick the Greek. Nick was a bona-fide local character. The Chronicle even ran a story on him when he retired. He’d emigrated from Greece and regularly sent money back to family members. When I left town for college, Nick told me he’d put four of his nephews through school in Greece. But growing up we were interested in his shop for other reasons.

One was his collection of hemi- demi- soft-porn. These were pulp paper, comic book-like publications featuring big-busted women and horny men. We seldom got our shoes shined, but we invented various excuses that enabled us to spend at least a few minutes in Nick’s shop, stealing looks at his stash.

One of our excuses centered on the bicep of Nick’s right arm. Years of buffing shoes had built that muscle into the kind of bulge that body-builders take steroids to create. Nick could be prompted to display the muscle, sometimes as a threat and sometimes as a brag, and we delighted in figuring out how to get him to flex and wiggle it.

I distinctly remember that a full shine—which included cleaning the shoes, at least three coats of high-quality paste wax, multiple passes with the cloth he’d loudly snap, energetic brushing, and dark-dye edge dressing—cost twenty-five cents. Nick was single, lived alone in an apartment above the Elks Club, ate simply, and turned those twenty-five cent sales in to tens of thousands of dollars. His only indulgences were a purple silk suit, a fancy fedora, and periodic train trips to one of the nearby big cities to visit his “girlfriends.”

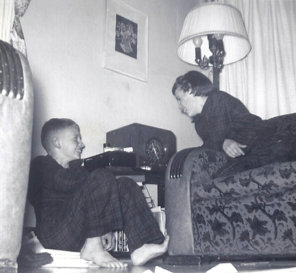

For most of my boyhood, my electronically mediated entertainment consisted of radio shows—Tom Mix, Sky King, Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders. I had a radio in my bedroom and convinced my folks to let me run 150 feet of copper wire along our roof line, across the back yard, and atop the garage, as an antenna . It worked surprisingly well. Some nights, probably because of the broadcast waves bouncing off the ionosphere, I was able to listen to disk jockeys from over a thousand miles away. I remember that I heard the first ads for pizza over that radio, from Shaky’s Pizza Parlor in Sacramento.

TV came in earnest to our town in 1951, but my family didn’t get our first set, a Sylvania halo-light console, until the mid-50’s. Our viewing was limited to the kids’ show, Wunda-Wunda for thirty minutes at noon, and evening shows selected by the grown-ups. My earliest memories are of the Ed Sullivan, whose variety show ran from 1948 to 1971. Sullivan himself was a partly-hunched over, long-faced, slow-talker whose character begged for impersonation, but he his show had the stature to attract top acts every week. The Beatles’ US debut was just one example. Lawrence Welk was also popular, along with game shows starring Groucho Marx, Bill Cullen, Jack Barry, and Bob Barker.

TV came in earnest to our town in 1951, but my family didn’t get our first set, a Sylvania halo-light console, until the mid-50’s. Our viewing was limited to the kids’ show, Wunda-Wunda for thirty minutes at noon, and evening shows selected by the grown-ups. My earliest memories are of the Ed Sullivan, whose variety show ran from 1948 to 1971. Sullivan himself was a partly-hunched over, long-faced, slow-talker whose character begged for impersonation, but he his show had the stature to attract top acts every week. The Beatles’ US debut was just one example. Lawrence Welk was also popular, along with game shows starring Groucho Marx, Bill Cullen, Jack Barry, and Bob Barker.

Can It Still Happen?

Combat games, secret forts, weapon-building and shooting, China Creek, bike racing and jumping, spying on the girls, soap box racing, swimming, Nick the Greek, radio, and later TV shows didn’t fill all our non-school time. We also had chestnut and walnut harvest and roasting, strawberry and blackberry picking, fishing in various local lakes, pickup basketball at the grade school playground, football on grassy vacant lots, and baseball wherever a group of us congregated. Plus, we passed the time tearing apart salvaged machinery and building our own ingenious inventions, customizing our bikes with spray paint & cheap accessories, and hanging around the local chain saw repairman, gas station, upholstery shop, bike store, and my family’s mom-and-pop grocery.

Looking back, I’m amazed at how educational a lot of these past times were. Just by looking and listening, I learned how to mix gas and oil for a two-cycle engine at the chainsaw repair place across the street. Service station mechanics cursed knowledgeably about flat tires, worn brakes, clogged air cleaners, and dozens of other mechanical challenges. The curmudgeon at the bike shop sharply criticized us for believing that, since there was an oil cup on a bike’s coaster brake, you should put oil in it. “Hell no!” he said. “That cup is no more useful than tits on a boar!”

Sure, we sometimes complained that we were bored, but the truth is, there was just about always something to do, even when it had been raining for days. At those times, the street drains were clogged with leaves and the intersection floods needed to be cleared with a rake so the water could swoosh down the grate, threatening to take us with it. We didn’t miss smart phones, video games, or Ipads. Most of our recreational activities stimulated our imaginations, and many taught us practical problem-solving, two mental capacities that, research says, are crippled today by media multitasking.

So what’s to be learned from this reminiscing? Obviously we can’t retract the digital revolution, and we wouldn’t want to. But neighborhoods still have all the complexities of trees and bushes, retailers and craftspeople doing interesting jobs, parks and playgrounds, sidewalks for bike-jumping and often streams and bridges to explore. Kids can be taught to navigate busy streets safely, avoid sexual predators, and exploit strength in numbers without vandalizing. Screens can be reserved for special times, school research, and connections with friends and family. It’s not just nostalgia to teach kids—better yet, to show them—that there are dozens of possibilities for fun surrounding them wherever they live.