When Oscar host Neil Patrick Harris mocked the whiteness of the 2015 awards, some viewers were offended, but most of those whose heads were out of the sand for at least part of the previous year recognized that Harris’ writers had just googled what’s trending. All the media outlets, from the New York Times to The Huffington Post and thenation.com have been publishing blogs and articles about Whiteness that build audiences for speakers who range from angry activist Tim Wise to academic philosopher Linda Martin Alcoff. These spokespeople, along with authors like Debby Irving (Waking Up White and Finding Myself in the Story of Race) are helpfully informing and inciting campus and community audiences all over the country.

A few weeks after the Oscars, the U. S. Department of Justice’s Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department described one main reason why Whiteness is such a crucial issue. “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices overwhelmingly impact African Americans,” the DOJ reported.

Data collected by the Ferguson Police Department from 2012 to 2014 show that African Americans account for 85% of the vehicle stops, 90% of the citations, and 93% of thearrests made by FPD officers, despite comprising only 67% of Ferguson’s population.[1]

Blacks, Latino/as, Native Americans, and other under-served people have known for many decades about the sharply tilted playing field that Whiteness creates not only in law enforcement but also in education, lending, voting, housing, business, and most other life arenas in the U. S.

As people of color intimately know, for almost two centuries, federal and state governments helped create the worst of these problems. The “self-evident truth” in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” certainly didn’t apply to slaves. And the clause, “We, the people of the United States” that begins the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution also meant only white, property-owning males.

Until relatively recently, only a few have commented on this stunning hypocrisy. One was the French researcher Alexis De Tocqueville who, after completing the first thorough sociological study of the U.S., wrote in 1865,

“An old and sincere friend of America, I am uneasy at seeing Slavery retard her progress, tarnish her glory, furnish arms to her detractors, compromise the future career of the Union which is the guaranty of her safety and greatness, and point out beforehand to her, to all her enemies, the spot where they are to strike. As a man, too, I am moved at the spectacle of man’s degradation by man, and I hope to see the day when the law will grant equal civil liberty to all the inhabitants of the same empire, as God accords the freedom of the will, without distinction, to the dwellers upon earth.”[2]

Government-sponsored discrimination has been sustained in the U.S. through, for example, the many laws establishing and protecting slavery and Jim Crow, the G.I. Bill as it was implemented, and all legislation about racial identity up to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Today, it includes national and state “English only” legislation, demands for laws guaranteeing “secure borders,” and efforts to weaken voting rights. But few of us white folks have learned about these parts of our national story, not only because our teachers and textbooks ignored them, but also because they were silenced by the power we exercised just by being White. No wonder W.E.B. Du Bois’ comment about the 20th century is equally true in the U.S. today: “The problem . . . is the problem of the color line.”[3]

I’m a white male who enjoys all kinds of privilege, and who’s blessed by acquaintances and friendships with several persons on color. Thanks to them and to considerable exploring and reading, I’m learning some important lessons about today’s version of this challenge. I haven’t made it all that far—which is why I call these “basic” lessons. But I’m learning these lessons from a perspective that might be understandable —and palatable—to many people who look like me and who are still unaware and/or puzzled. So I’d like to offer a contribution to the conversation about what is currently the most important challenge U.S. culture faces: The need to understand and act on the damning and tragic impact of Whiteness.

Lesson #1: Whiteness Is the Problem

As diversity expert Verna Myers puts it in a popular TED-X talk, “We gotta get out of denial.” So many of us Whites believe that “We don’t have a racist bone in our bodies,” and “We are colorblind,” that it’s difficult to see the problem as it actually exists. People of all racial identities live with prejudices; they’re part of the psychological makeup of every cultural group. For example, Myers, who is female, feminist, and Black, tells the story of hearing a woman’s voice make the standard announcement from the cockpit at the beginning of a cross-country flight and then, when the plane was lurching through scary turbulence, wishing to God that the pilot was a man. This is prejudice, and we all rely on it to evaluate short people and tall ones; a woman in a miniskirt or a hijab; the skin color and facial features of Blacks, Asians, Latino/as, and Whites; and, according to a Chevy ad, a guy standing next to a car vs. a truck.

There’s an important distinction, though, between prejudice and systemic racism. Black feminist author bell hooks clarifies why systemic racism can only be enforced by those who belong to the group in power. She asks,

Why is it so difficult for many white folks to understand that racism is oppressive not because white folks have prejudicial feelings about blacks (they could have such feelings and leave us alone) but because it is a system that promotes domination and subjugation? The prejudicial feelings some blacks may express about whites are in no way linked to a system of domination that affords us any power to coercively control the lives and well-being of white folks. That needs to be understood. [4]

This reality about the power of Whiteness has escaped many of us who believe that we “don’thave culture,” and that “the problem” belongs to those who do—Blacks, Latino/as, Native Americans, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Caribbean Americans, etc. It’s crucial to acknowledge that White is also a cultural color and that in the 21st century U. S., “the normative violence of Whiteness”[5] is an issue that needs to be recognized, problematized, criticized, and put in its place by everyone.

We need to do this because, currently, as I noted, the playing fields are anything but level. The status quo is sharply skewed in the direction of Whites.

What evidence supports this claim? I’ve already mentioned federal and state laws and policies that have reinforced discrimination for over two centuries. They’ve had a huge impact on general economic indicators. U.S. census data report that between 10% and 14% of Whites live in poverty, and the same figures for Blacks are 37% to 55% and 26% to 40% for Latino/as. Currently, 5% to 6% of Whites are unemployed, about 17% of African Americans, and over 40% of Pacific Islanders. The median household income of Whites is close to $85,000 a year; Latino/a families earn about $32,000 a year; and Blacks are the lowest racial group at just over $20,000.[6] Can Whites seriously claim that these differences are due mainly to the fact that most people with skin tone different from ours are lazy, uneducated, or incompetent?

Demographic data flesh out the economic story. Some of what today’s Black families are up against began when their grandfathers returned from helping win World War II and tried to take advantage of the G.I. Bill. While there is nothing discriminatory in the language of the Bill itself, it was applied in racist ways across the country. For example, by October 1946, 6,500 former soldiers had been placed in nonfarm jobs by the employment service in Mississippi; 86% of the skilled and semiskilled jobs were filled by whites, 92% of the unskilled ones by blacks. And this pattern didn’t just occur in the South. In New York and northern New Jersey, ”fewer than 100 of the 67,000 mortgages insured by the G.I. Bill supported home purchases by nonwhites.”[7] Parallel problems plagued applications of the educational support provisions of the Bill. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, “the G.I. Bill exacerbated rather than narrowed the economic and educational differences between blacks and whites among men from the South.” [8]

The racist application of home financing policies continues today. In 2011, Countrywide Finance was fined $335 million by the Department of Justice for forcing subprime loans on Hispanics and African Americans. One year later, Wells Fargo & Co. agreed to pay $175 million to resolve allegations it charged African-Americans and Hispanics higher rates and fees on mortgages even when they qualified for better deals.[9] The U.S. Department of Justice reports that in 2014 alone, they filed complaints or entered consent orders with half a dozen banks for charging Black and Hispanic customers higher rates than they charged Whites.[10]

Tim Wise[11] explains that these data are especially significant, because they reveal important reasons for racial disparities not just in income but in wealth. The most significant part of most U.S. families’ net worth is their home. It represents the largest investment and, except in deteriorating neighborhoods or recession periods, a well-maintained home’s value increases at least as much as inflation. Home equity is used to finance college educations and other wealth-building investments. What happens to a group that is systematically denied the opportunity to invest in prime real estate by redlining and other discriminatory practices and that is offered only subprime loan packages by discriminatory lenders? These families can’t build the wealth that white folks accumulate by investing in starter-homes in desirable communities and growing their equity gradually. This is one significant reason why poverty statistics are so racially skewed.

And consider how discrimination in hiring still helps tilt that part of the playing field. You would think that, if a resume accurately records impressive experiences and qualifications that fit a job description, it ought to be put in the “interview” pile. But not apparently, if the name on the resume appears to be non-white. In 2003, a National Bureau of Economic Research team

respond[ed] with fictitious resumes to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago newspapers. To manipulateperception of race, each resume [was] assigned either a very African American sounding name or a veryWhite sounding name. The results show significant discrimination against African-American names: White names receive 50 percent more callbacks for interviews. We also find that race affects the benefits of a better resume. For White names, a higher quality resume elicits 30 percent more callbacks whereas for African Americans, it elicits a far smaller increase.[12]

Data coming from another direction demonstrate that, “When it comes to illegal drug use,” as The Huffington Post reports, “White America does the crime, Black Americans get the time.” Nearly 20% of whites have tried cocaine, as compared with 10% of Blacks and Latinos, and higher percentages of Whites have also tried hallucinogens, marijuana, OxyContin, and meth. But Blacks are arrested for drug possession nearly three times more than Whites.[13]

The Department of Justice report on Ferguson is only the most recent example of the decades-old trend of local, state, and national law enforcement’s treatment of persons of color. When New York City’s mayor discussed “the talk” that parents of color know is a necessary part of the parenting of every[14][15] Black, Brown, or mixed-race child (“Whenever you’re confronted by an officer or other white authority, here’s the way you should behave:”), he was castigated by law enforcement officers for simply telling the truth.

More proof exists in the demographics of people in power. Despite the fact that voters elected an African American President twice, and Oprah is indeed a billionaire, the overwhelming majority of persons in power in the U.S. in 2015 are still white. Local, state, and national lawmakers; judges; teachers; principals; superintendents; CEOs and CFOs; firefighters; law-enforcement officers; NBA, NFL, and MLB coaches; symphony conductors and most other leaders are not persons of color.

In short, gay-bashing is still a problem, women still earn less than men in the same job, and people with disabilities still suffer discrimination. But all the demographic data and the thousands of stories about microaggressions make it clear that, in the U. S., at this time of our history, the biggest reason that the playing field is steeply tilted is race. Lesson #1 is to face the fact that the playing field is not level, and to learn about and take action to remediate its consequences.

Lesson #2: Equity Doesn’t Mean Equality

People who want to do something about the kinds of problems I’ve just described tend to call themselves “racial equity workers.” This label clarifies not only that their first focus is on the racial dimensions of the challenge but also that their primary goal is to enhance equity. Some who are new to the conversation wonder exactly what this means.

The first dictionary definition of the word, “equity” is “The state, quality, or ideal of being just, impartial, and fair,” and this is the focus of racial equity work.

Why does this focus create problems? Because freedom and equality are two of the most basic U.S. values, and when we start with a status quo that is markedly unfair, a playing field that is anything but flat, equity demands unequal remedies that threaten some individual’s freedoms. You can’t level a tilted playing field by giving everybody the same amount of help. This would just keep the field uneven. In order to move toward equity—justice and fairness–some has to be transferred from those of us who have more to those who have less. If this sounds un-American, remember that equity is the rationale behind the structures of the graduated income and inheritance taxes. They both treat people unequally, and appropriately so.

One segment of the 2015 Oscars provided a memorable example of this principle. When the rapper named Common and musician John Legend performed their Oscar-winning song, “Glory,” the staging featured a crowd reenacting the march across the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Like the original marchers in 1965, the Oscar performers included both Blacks and Whites. But only the Blacks sang. The Whites showed up as allies; they were there to embody support for Black voices. And they stayed in the background. They enhanced equity by being treated unequally, by taking a back seat to the people who, in this instance, matter most.

This is the kind of action Whites most need to take: Listen to people of color rather than talking at, or down to them. Offer to join initiatives controlled by people of color and ask, “How can I help?” Butt out, when asked. Recruit underrepresented collaborators and take subordinate positions. Practice humility by holding your own cultural identifiers lightly, rather than with white knuckles. These are all ways to intentionally practice ally skills—curiosity about other cultures, deference, respect, and applying not just the Golden Rule but the Platinum Rule (Do unto others as they would have you do unto them).[16]

So long as the status quo, the real, objectively-describable, factual situation is one of significant power and resource disparity, us White folks’ job is to enhance not equality but equity.

Lesson #3: Be Curious About Your Own Culture and Others’

Curiosity begins with an open, interested, inquisitive mind-set. When a person’s being curious, she wants to know or learn. She’s wondering, and she’s asking genuine questions.

In the book, Curious? Discover the Missing Ingredient to a Fulfilling Life, Todd Kashdan explains that people tend to dismiss curiosity as a childish, naïve trait, but it can actually give us profound advantages. The reason is that curiosity helps us approach uncertainty in our everyday lives with a positive attitude. “Although you might believe that certainty and control over your circumstances bring you pleasure, it is often uncertainty and challenge that bring the longest-lasting benefits,” Kashdan says. By wielding curiosity actively, “we can create a more fulfilling life.”[17] This is because each of us experiences moments every day that we can explore or ignore. When we explore them, we can have experiences that expand and enrich us. You can mobilize curiosity to help with situations of difficult difference by focusing it first on yourself and then on others.

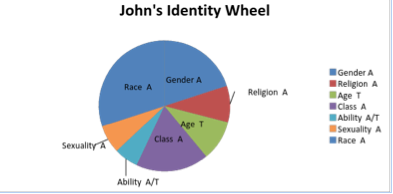

Taking Your Own Cultural Inventory. In this case, being curious about yourself means taking your own cultural inventory. One way to do this is to draw an “identity wheel.” You begin with a circle representing the whole you, and you divide the circle into seven pie-shaped pieces that identify your race, gender, religion, class, ability, sexuality, and age. The size of each slice reflects your awareness of that part of your identity. If you’re very aware of your race or religion, that slice is larger than those you are less aware of. And so on.

The second step is to identify which parts of your identity help you be advantaged, and which make you culturally targeted—a potential victim of oppression—by putting an “A” or a “T” in each segment.

Each person’s identity wheel changes from situation to situation, as he or she becomes more or less aware of various segments. As I write this, though, my identity wheel looks like this:

I am most aware of being white and male. My socio-economic identity as middle class is next in significance to me, and then comes my age. The significance of my religion and heterosexual identity change from situation to situation, as you’d expect, and I’m usually least aware of my disabilities, even though I’m hearing-impaired enough to wear two hearing aids. They work well enough to keep this element of my identity relatively out of my awareness. All the main elements of my cultural identifiers help me be advantaged, except for my age, which occasionally puts me in the position of being targeted. There are times when my hearing is a disadvantage, but not very often.

If you’re serious about understanding Whiteness, you need to complete an activity like this. Until you’ve been intentionally and systematically curious about your own cultural identifiers, and until you’ve come to understand what it means to inhabit each of these cultures, you can’t go very far toward understanding white privilege.

Being Curious about Others. It’s also important to be curious about other(s), first, because of the way curiosity displaces defensiveness. It’s like the way gratitude displaces anger. When you’re feeling grateful it’s difficult to be angry at your situation or somebody else at the same time. Similarly, when you’re in a “Well, that’s interesting; I wonder what’s going on?” mode, it’s impossible, at the same time, to be accusing or attacking somebody.

Curiosity can also help bring out the best in other people. Just as defensiveness tends to elicit defensiveness, and anger encourages more of the same, people usually respond positively to curiosity. When someone takes an interest in who we are and the things we do, when they ask us genuine questions and behave in ways that show us they are sincerely curious about the things we care about us, we light up. People appreciate being treated as “an expert.”

One way to develop your more curious attitude is to pay attention to other cultures. I recently heard a Black speaker explain why many African American weddings start 30 minutes after the scheduled time, and why the bride and groom “jump over the broom.” A Black friend gave me insight into the “scary black male” image by explaining that, when he’s by himself waiting for an elevator, and the car that arrives contains only one white woman, he deliberately waits for another car. I’ve learned that some Blacks who’ve escaped “the projects” came away with a heightened sense of impatience about professional accomplishment fueled by the deep-seated recognition that they could well be dead before they’re thirty. I learned what “Keeping it 100” means from Stephen Colbert’s replacement, Larry Wilmore. The other primary way to develop your curiosity about someone from a culture different from yours to ask them how they’d like to be treated. You could predict their preference, but this would have to be based on your knowledge of some track record of what they’ve liked in the past, perhaps acquired from a friend of theirs or your own experience with them as a friend. If you can’t ask, then perhaps you’re not so much treating them ethically as guessing what they’d like.

As Bill Puka summarizes,

Without involving others, such role-taking is a unilateral affair, whether well-intended or otherwise. It is often paternalistic, choosing someone’s best interest. The whole process is typically done by oneself, within one’s self-perspective or ego, and it can be spun as one wishes, no checks involved. Fairer and more respectful alternatives would involve not only consulting others on their actual outlooks, but including them in our decision-making. “Is it OK with you if….” This approach. . .is based on a different sort of mutuality, democratizing our choices and actions so that they are multilateral.[1]

Lesson #4: Substitute Response-ability for Guilt

“Why do you people always play the race card? I don’t condone slavery. I support civil rights. I can’t change what happened before I was born.” The dynamic that combines resentment from people of color and regret from well-meaning Whites commonly produces this kind of guilt. And it only makes problems worse.

If you live where snowfall is a winter reality, you don’t consider yourself guilty for the most recent 4”-6” of white stuff. And if you’re a renter or property owner, it is up to you to clear the snow from your sidewalk. Although you had nothing to do with creating the problem, you are expected to help deal with it. This is an example of response-ability; not “fault” but the willingness and ability to respond to the conditions you encounter that need to be changed.

Each of us needs to understand the realities and the crushing weight of Whiteness and to respond effectively in our own spheres of influence. “Understanding” is how we think globally and “responding effectively” is how we act locally.

When I say “Each of us,” I mean both Whites and people of color. You only need to reflect a little on the multi-racial adoration of Michael Jackson and Beyonce to realize that, especially because the power difference is so great, White values shape both white and Black consciousness, often insidiously.

Both Jackson and Beyonce have invested millions in becoming what mainly White standards say is attractive and sexy. We all have a lot to learn about Whiteness, and it works best when we learn it together, because we can be teachers and learners with each other.

I’ve already mentioned several ways to build understanding.

● Read about Whiteness. One must-read is Dr. Peggy McIntosh’s classic, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.”[18] If you google Whiteness Books, you’ll get over a million results. “Whiteness Websites” will give you 220,000 more. “Microaggressions” and “Meritocracy” are two other topics you might want to learn more about.

● Talk about race. Not talking about race is a privilege only available to white people. It’ll help if you’ve thoroughly completed an identity wheel, and you’ll need to enter the conversations with humility, holding your own racial identifiers lightly. But invite the people of color in your life and Whites who share your curiosity to converse with you about questions you have—and more importantly, questions they have. It won’t always be comfortable. And it’ll definitely help.

● Attend a workshop or conference. The National White Privilege Conference is in its 15th year. Other helpful meetings are held by the Pacific Educational Group, the National Equity Consortium, The Center for the Study of White American Culture, and many other academic and non-academic organizations. International conferences have also been held recently in London, Dubrovnik, and Warwick.

● Volunteer for an organization in your community that serves people of color. When you do, carefully guard against The Robin Hood Syndrome or “dysfunctional rescuing,” the patronizing impetus that comes from a determination to “Help those unfortunate folks.” Realize that you have more to learn from them then they’ll learn from you.

● Participate, as a member or ally in the local NAACP, LULAC, or other civil rights group. “As an ally” means as a listener more than a talker, with respect and curiosity, and ready to both give and be a learner. Attend events they sponsor. Explore becoming a member. Butt out when asked.

● Do equity work in your own sphere of influence. In your extended family, at work, among friends, at the health club, take advantage of every opportunity to cite a positive counter-example, invite another way of thinking, provide factual information, and refuse to tolerate microaggressions or subtly racist comments. This is especially important to those who are members of leadership groups—boards of for-profits and nonprofits, chambers of commerce, service organizations.

CONCLUSION: IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT YOU

Why pay any attention to these lessons? Especially if you’re white, why bother with Whiteness? Why risk your comfort, your positional power, your boundaries, your cultural expertise? Ultimately, because it’s really not all about you—or me.

If you’re a spiritual or religious person, you’re familiar with the realization that there’s a power larger than you that needs at least your attention, alignment of your everyday practices, and preferably your deference, your commitment, and even your worship. The texts and traditions of the three Abrahamic faiths make it clear that the people who belong to God, Jesus, or Allah are supposed to be collaborating in peace, not abusing or killing each other. Humans are created to celebrate diversity not to ram beliefs down each other’s throats. You learn about Whiteness and act to remedy its impacts because all spiritual programs and religions encourage it.[19]

If you’re not spiritual or religious, and you are white, you have a couple of options. One is to take these lessons to heart for self-survival. Whites are already a minority in several states, and the best estimates are that we’ll be outnumbered throughout the U.S. by 2044.[20] Think how much easier it will be to thrive in this environment if you’ve already worked through its challenges.

A second reason is that genuine diversity is good for organizations and for business. Although most people feel more comfortable in groups made up of people like them, heterogeneous groups have been shown to be better at decision-making and problem-solving. Diversity itself “triggers more careful information processing that is absent in homogeneous groups.”[21] In the U.S., businesses that welcome and support their employees who are Muslim, Buddhist, Hispanic, and disabled also experience less turnover, which is always expensive. And their customers/clients appreciate purchasing goods and services from people who look like they do.

But ultimately, the reason to pay attention to these lessons, and to others like them, is simple: In the U.S. at this time of the 21st century, it’s simply the right thing to do.

[1] http://www.iep.utm.edu/goldrule/

[1] U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Investigation of the Ferguson Police

Department. March 4, 2015, p. 4.

[2] Alexis De Tocqueville, Oeuvres completes, Gallimard, T. VII, pp. 1663–1664.

[3] W. E. B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk, Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1903, Introduction.

[4] Bell hooks, black looks: race and representation, Routledge, 2015, p.13.

[5] C.M. Nelson, “Resisting Whiteness: Mexican American Studies and Rhetorical Struggles for Visibility,” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 8 (2015), 63-80.

[6]http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html

[7] Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America. Norton, 2005.

[8] http://www.nber.org/digest/dec02/w9044.html.

[9] (http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/12/us-wells-lending-settlement-idUSBRE86B0V220120712).

[10] http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/hce/whatnew.php

[11] http://www.timwise.org/

[12] http://www.nber.org/papers/w9873

[13] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/17/racial-disparity-drug-use_n_3941346.html

[16] https://johnstewart.org/blog/2014/10/23/platinum-empathy.html

[17] https://psychologies.co.uk/self/curiosity-the-secret-to-your-success.htm

[18] http://amptoons.com/blog/files/mcintosh.html

[19] When IS, Boko Haram, Kingdom Identity Ministries, and other hate groups attempt to ground their violence in sacred texts, they radically distort the beliefs they cite.

[20] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2875786/White-people-minority-2044-thanks-ageing-population-Hispanics-make-quarter-U-S-citizens.html

[21] http://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/better_decisions_through_diversity