John Stewart & Tiye Sherrod

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2014 AT 7:34AM

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2014 AT 7:34AMRemember the last time you were in a situation with somebody who is different from you in some significant way, and you felt fear, anger, defensiveness, resentment, or maybe even the urge to be violent? If you’re a black woman it could have been when your white male manager started making over-friendly comments about how you look and you were disgusted and worried about how to respond. Or if you’re gay, it might have happened when someone learned of your sexuality and asked, “I don’t mean to be too personal, but have you ever had normal sex?” and you were enraged. Or, if you’re a white woman, maybe it happened when you saw a black male with dreadlocks walking toward you on a city street and you were afraid.

One natural tendency in every situation like this is “fight or flight.” You report the manager to his superior, aggressively ridicule the offensive question or cross the street. In some cases, these can be the safe, appropriate, right things to do. And in many other situations that don’t threaten your well-being and that still involve difficult differences, there’s another option.

This other option can be helpful when you’re around someone who’s culturally different from you and you’re irritated at how loudly they are talking, how close they’re standing to you, or how they don’t seem to notice that you’re competent and you suspect it’s because you’re female, Latino, physically disabled, or Black. Or when you are one of the only people in the room like you, and you notice that most of the others are ignoring you. Or when you’re stopped at a stop sign and a young person who’s not your ethnicity slowly saunters in front of you, seeming to deliberately make you wait. Or you’re passed over for a reward at work in favor of a person who’s culturally different from you. Or you encounter an obvious act of discrimination that you want to respond to—a comment about “queers” or “fags,” ridicule of a woman in power, or violent criticism of “those Muslims.”

New Default Responses

This neither-fight-nor-flight option is made up of three responses, and when they’re done well, this set of responses can keep you safe, communicate respect, and preserve your dignity. In the best cases, they can help not only defuse the situation but also enable you and the other people to learn some important things about yourselves and each other.

We want to invite you to consider developing these three response options to the point where they become automatic each time you experience a difficult difference. The idea is for you to make these three your default response options.

The Challenge.

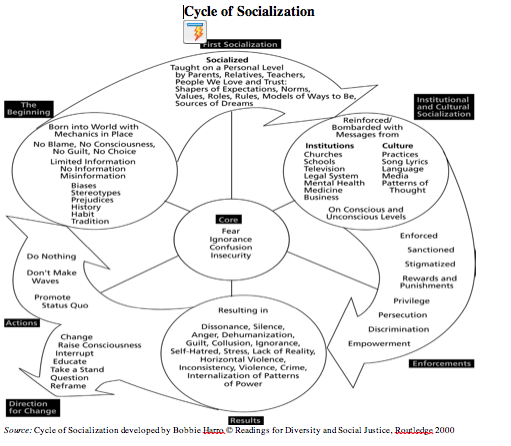

In the beginning, each of the three will require conscious effort. You’ll have to work to get them to become even close to automatic. This is because all of us have grown up in a “Cycle of Socialization” that leaves us believing deeply that our own cultural way of doing things is “the right way.” We are born without awareness of cultural differences and without racist or sexist attitudes, values, or beliefs. We acquire attitudes, values, and beliefs that support various “-isms” through a socialization process that is often more subtle than overt. From our earliest experiences, we learn lessons about our own and other groups through listening to and observing our parents and family. As we move out into the wider world, we take in lessons from our society and its institutions that socialize us to internalize and take for granted, for example, racialized norms, values, and assumptions.[1]

Source: Cycle of Socialization developed by Bobbie Harro © Readings for Diversity and Social Justice, Routledge 2000

This diagram shows how the cycle works. From “The Beginning,” (at the 10 o’clock point on the circle), “First Socialization” happens as family, peers, and community exert the most powerful early socializing influences. On the topics of race or ethnicity, white parents, peers, and community may reinforce fear or avoidance of people of color and instill beliefs that white values and standards are the correct norm to follow and to use in judging others. Parents, peers, and communities of color may teach children to avoid interactions with white people, to adjust to the standards of white society for their own protection, or to contain their feelings in situations that are racially dangerous.

Then “Institutional and Cultural Socialization” happens as these early messages are reinforced through contact with institutions, including all the ones listed in the diagram. Everybody learns that powerful people are mostly white (such as Congress, police officers and judges, teachers, doctors, news commentators, and historical figures studied in school). We internalize assumptions that white people are the ones who make history and are those “naturally” in positions of power and influence. Whiteness unconsciously becomes the standard of normality

The combination of messages that we receive from our families, our communities, the surrounding culture, and the institutions of society creates what is listed under “Results”—a social system based on the “Rightness of Whiteness” and of primarily male, heterosexual, and able people. This is how the Cycle of Socialization creates ethnocentrism.

As the diagram also shows, new information can help us become conscious of how we’ve become socialized and empower us to choose different attitudes, assumptions, and behaviors. This is our goal. This is what the new default response options can do for you.

Directions for Change: Curiosity, Humility, Platinum Empathy

The three responses that make up this new default response are Curiosity, Humility, and Platinum Empathy. Together, they make up what we’re hoping will become your new, automatic way of responding whenever you experience difficult difference.

The basic meaning of all four of these words is pretty clear. But individually, they are profoundly different from the automatic responses of most U.S. citizens to situations of difficult difference, and when put together, the three practices sound, look, and feel a whole lot different from what people of most U.S. cultures usually do.

So this is an invitation not only for Whites who are in power, but also for African Americans, Latinos and Latinas, Jewish people, disabled people, women, Asian-Americans, Native Americans, and everyone who experiences difficult differences. You may decide to refuse the invitation and to stick with your current, probably ethnocentric responses. Realize, though, that the more people in the U.S. keep doing what we’ve been doing in our intercultural contacts, the more likely that we’ll continue to hear about—and experience—events like the Michael Brown shooting in Furgeson, Missouri, the Trayvon Martin shooting in Sanford, Florida, the September 14, 2014 gay bashing in Philadelphia, and similar cultural violence. To the degree that people make these three their default response options, the number and seriousness of difficult differences will shrink, across U.S. culture.

Curiosity

Curiosity begins with an open, interested, inquisitive mind-set. When a person’s being curious, she wants to know or learn. She’s wondering, and focused on asking genuine questions.

In the book, Curious? Discover the Missing Ingredient to a Fulfilling Life, Todd Kashdan explains that people tend to dismiss curiosity as a childish, naïve trait, but it can actually give us profound advantages. The reason is that curiosity helps us approach uncertainty in our everyday lives with a positive attitude. “Although you might believe that certainty and control over your circumstances bring you pleasure, it is often uncertainty and challenge that bring the longest-lasting benefits,” Kashdan says. By wielding curiosity actively, “we can create a more fulfilling life.”[https://psychologies.co.uk/self/curiosity-the-secret-to-your-success.html] This is because each of us experiences moments every day that we can explore or ignore. When we explore them, we can have experiences that expand and enrich us. You can mobilize curiosity to help with situations of difficult difference by focusing it first on yourself and then on others.

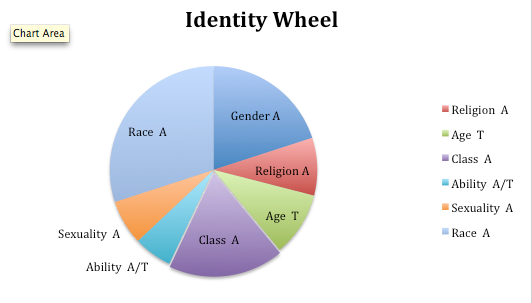

Taking Your Own Cultural Inventory. Being curious about yourself means taking your own cultural inventory, identifying how the Cycle of Socialization has affected you. One way to do this is to draw an “identity wheel.” You begin with a circle representing the whole you, and you divide the circle into seven pie-shaped pieces that identify your race, gender, religion, class, ability, sexuality, and age. The size of each slice reflects your awareness of that part of your identity. If you’re very aware of your race or religion, that slice is larger than those you are less aware of. And so on.

The second step is to identify which parts of your identity help you be advantaged, and which make you culturally targeted—a victim of oppression—by putting an “A” or a “T” in each segment.

Each person’s identity wheel changes from situation to situation, as he or she becomes more or less aware of various segments. As John writes this, though, his identity wheel looks like this:

John is most aware of being white and male. His socio-economic identity as middle class is next in significance to him, and then comes his age. The significance of his religion and heterosexual identity changes from situation to situation, as you’d expect, and he’s usually least aware of his disabilities, even though he is hearing-impaired enough to wear two hearing aids. They work well enough to keep this element of his identity relatively out of his awareness. All the main elements of his cultural identity help him be advantaged, except for his age, which occasionally puts him in the position of being targeted. There are times when his hearing is a disadvantage, but not very often.

Another way to take your cultural inventory is to develop a bulleted list of five of your cultural identities and at least three examples of what each means in your life. In this case, you choose which five are important. Tiye’s list would look like this:

- Black African American

- Must work harder to prove value

- Constantly aware of how my actions look toward my race

- Fear of Speaking Freely without judgment

- Female

- Must constantly be wary of my safety

- The intersectionality of being female and black (Angry Black Woman)

- Adult

- Being unapologetic for being a leader

- People respect my opinion as being valid

- More economic opportunity because I’m not ‘old’

- Heterosexual

- Be an LGBTQ ally

- Not afraid of ridicule, or being with a partner openly in public

- Cultural Equity Activist

- “Show up” at every opportunity to support cultural equity events & peopl

- Advocate for those who can’t advocate for themselves

- Challenge those in privileged groups when words or actions are oppressive

- Advocate for those who can’t advocate for themselves

You can see how this would go for you. The number five is arbitrary, but it’s important to recognize that we’re all multicultural beings, and to understand what each of our identities means. It’s also important to remember that different parts of our identities surface in different situations.

Each person should complete at least one version of an identity inventory before going further in this project. Until you’ve been intentionally and systematically curious about your cultural identities, and until you’ve come to understand what it means to inhabit each of these cultures, you can’t go very far toward developing this new default response option.

Being Curious about Others . In a situation of difficult difference, it’s also important to be curious about other(s), first, because of the way curiosity displaces defensiveness. It’s like the way gratitude displaces anger. When you’re feeling grateful it’s difficult to be angry at your situation or somebody else at the same time. Similarly, when you’re in a “Well, that’s interesting; I wonder what’s going on?” mode, it’s impossible, at the same time, to be accusing or attacking somebody.

Curiosity can also help bring out the best in other people. Just as defensiveness tends to elicit defensiveness, and anger encourages more of the same, people usually respond positively to curiosity. When someone takes an interest in who we are and the things we do, when they ask us genuine questions and behave in ways that show us they are sincerely curious about the things we care about us, we light up. People appreciate being treated as “an expert.”

Interestingly, one key to developing a more curious attitude is to recognize the moments you feel uncomfortable. Kashdan writes, “When you’re avoiding a situation, it’s a good sign that there’s something novel there, something uncertain, and you can take advantage of that to experiment.” For many of us, conversations with people different from ourselves can be particularly awkward, so they are an excellent place to start.

A curious rather than a defensive response to the experience of being passed over for a reward at work in favor of a person who’s culturally different could start with a request for a meeting with the decision maker. You could ask him or her, “What are the main criteria that you use to decide who gets promoted?” You might also ask, “What do you see me doing well, and what do you think I could do better?” Or “As you know, I’m interested in moving up in the department, and I wonder if you can give me some suggestions about how I can help that happen.” A conversation that starts with these questions is almost guaranteed to give you important information about why you didn’t get the promotion you thought you deserved. And, given the commitment of most companies to equitable treatment of employees, it’s also likely to help you understand why, from the manager’s perspective, his or her decision made sense and was not discriminatory.

The situation where you overhear a comment about “queers” or “fags” or ridicule of a woman in power can be more difficult. If you question the person making the comment in public, he or she is almost guaranteed to respond with defensiveness and anger. It’ll work better to be curious later, and in private. When there’s no audience around, you might try, “I was uncomfortable with what you said about ‘queers and fags,’ and I wonder what you were trying to accomplish?” Depending on how the person responds, you might follow up with, “I think that’s inconsistent with the company’s policies about LGBT people, do you?” Or, you might try, “I think ____(an out LGBT person)___ contributes a lot to marketing; are you aware of what he/she’s done?” Or, “I appreciate how much you contribute to what we do around here,and I wonder how you think those kinds of comments are helpful.”

The point is to respond to the difficult difference with an inquiring mind-set and genuine questions rather than attacks, sarcasm, or defensiveness. Sometimes, your curiosity will be put down with another attack. Sometimes the other person will ignore you or walk away. And sometimes, especially when it’s paired with humility and platinum empathy, curiosity can lead to a genuinely helpful conversation.

Humility

Humility basically means holding a modest opinion of your own importance. It means having a clear understanding of, and respect for, your own place in a situation. Humility is the opposite of what the Greeks called hubris, which basically meant forgetting that you’re not a god. Remembering you’re not a god—so you’re as flawed as anybody else—can be the beginning of humility.

Because this word is connected with the Latin term for earth or ground (humus), some people think humility means being lowly or insignificant. But it really means being well-grounded, anchored in the clear realization that you are not the center of the universe. Despite what some entertainers, sports figures, and politicians seem to believe, it’s not all about me. Each of us plays more or less important roles in the situations we inhabit, depending on what they are and who else is around. When John’s children are in the room, he has some authority because he’s the dad, but in a group of singers he’s just a person who can barely carry a tune. And even when he’s dad, he doesn’t know even close to everything about his kids’ lives. So he needs to stay well-grounded in his own limitations.

Cultural humility is trickier than staying well-grounded in your family or at work, because, thanks to the Cycle of Socialization, most of us are pretty ethnocentric. We grow up learning a set of attitudes and behaviors that are held by people like us—Asian Americans, Whites in poverty, Black activists, wealthy Christians—and we uncritically accept these attitudes and behaviors as “normal.” As a result, almost everybody has to work to counter the ethnocentrism that we’ve unconsciously inherited from our home cultures.

On huge benefit of taking your own cultural inventory—either with the identity wheel or the “five identities” activity—is that you understand what you need to be humble about. In John’s case, he needs to learn to hold his whiteness, maleness, age, heterosexuality, and his activist commitments lightly.

By holding each cultural commitment lightly we mean that you understand that, since not everybody is male, for example, or heterosexual, you can expect that, if you are male and heterosexual, some of what you value, and what you believe is “normal” will not be valued or considered normal by others. When you live with this expectation, you’re not surprised to find yourself around somebody who’s “talking way too loudly,” ignoring people like you, or getting a promotion you think you deserved. And when you’re not surprised—when you actually expect these differences—you’re much less likely to respond defensively or aggressively toward them. Your response is something like, “OK, there’s a clear difference between us,” or maybe “OK, there’s an obvious difference that I didn’t expect,” rather than some silent or spoken version of, “I can’t believe you’re doing that!” or “Where did that crazy/offensive/immoral idea come from?!”

Importantly, holding each element of your cultural identity lightly does not mean that you have to abandon any of them. For example, even if he or she could, a white person wouldn’t have to give up their whiteness to have a fruitful conversation with a person of color. You just need to remember that your conversation partner doesn’t enjoy your unearned privilege. And, in this case, as the higher power person in the conversation, you have to accept your responsibility to be aware and respectful of this fact. To continue this example, the person of color can’t expect his ideas to be valued the same way you can expect yours to be; his ideas will be heard as “a Black man’s,” rather than as “a person’s” or “a man’s ideas,” and so on.

To take another difficult example, if “Christian” is part of your cultural identity, and if your Christianity leads you to disapprove of homosexuality, what might it mean to hold your Christian identity lightly in a conversation with an assertively “out” gay or lesbian person? As soon as it becomes apparent that you’re different in this way, you’re likely to experience an immediate “fight or flight” sensation. You’re going to want to change the subject quickly, show them the error of their ways, or get the heck out of there. This new default option presents a set of alternatives.

To operationalize humility in this case, you could start by reminding yourself that not everybody in the world is heterosexual. In fact, the most reliable estimates we’ve read indicate that 8% to 10% of the population is LGBT. So, realistically, it doesn’t make sense to be surprised that you find yourself talking to someone in this population.

Second, you can remind yourself that, although you think of homosexuality as a lifestyle choice, members of the LGBT community and their allies believe that they are born with these sexual preferences. Humility means that you can listen to someone who is gay carefully enough to understand why that person might feel it’s simply part of who they are, like being short or bald.

Third, you can remember that understanding doesn’t equal agreement. You can listen and learn about this person’s ideas and about parts of the LGBT world without putting this part of your own cultural identity at risk. You don’t have to defend your own sexuality or attack theirs.

Fourth, you can remind yourself of the advantages of diversity. It’s good to be tolerant of people different from you—“Live and let live.” And it’s much better to recognize how differences can strengthen groups. When a decision-making group includes people with diverse cultural perspectives, the products of the group are better than those produced by homogeneous groups. When organizations listen to the voices of their marginalized members, they adopt better policies and practices. And they also reduce turnover, which is a major expense. Diversity is good for problem solving and it’s also good for business.

We hope these examples give you a sense of what’s meant by the second of these three choices that we’re inviting you to develop into your default responses for situations of difficult difference.

Platinum Empathy

There’s an old story about the only living being that just about everybody in the world would agree was lovable—Abraham Lincoln’s dog, Fido. Empathy is kind of like that. Just about everybody agrees that being able to understand another person’s condition from their perspective, to “walk a mile in her moccasins” is a crucial interpersonal skill.

Empathic listening is the communication practice that actualizes this psychological skill. Executive trainer and best-selling author, Steven Covey (https://www.stephencovey.com/) argues that the greatest challenge for the empathic listener is adopting the necessary mind-set. It’s the mind-set of the person who, when he hears someone who disagrees with him, walks up to the person and says, “You see things differently. I need to listen to you.” It’s the mind-set of a person with the courage and humility to reach outside his or her own frame of reference.

Covey is so convinced of the importance of empathic listening that he’s

“. . .devoted much of my life to teaching [it]. . . . I liken empathic listening to giving people ‘psychological air.’ . . . Like the need for air, the greatest psychological need of a human being is to be understood and valued. When you listen with empathy to another person, you give that person psychological air. Once that vital need is met, you can then focus on problem-solving.”

The Potential Problem. Paying close attention to other’s feelings and thoughts, and listening empathically are useful interpersonal skills. John has emphasized their importance in U&ME: Communicating in Moments that Matter and both of us have encouraged empathy in our training and teaching.

When you’re in a situation marked by important cultural differences, though, an oversimplified understanding of empathy and empathic listening can create real problems. Yesterday, for example, John was talking with an African American friend about his job search, and he sensed a real sense of impatience coming from him that he thought could create problems. If he acted on his impatience, John worried, he could shoot himself in the foot with possible future employers. John was empathic enough to sense his feeling of edginess, and his experience told John that his feeling could get him into trouble.

When John shared his concern, his friend explained why John really wasn’t understanding him. The friend had grown up in the projects in Cleveland, and never expected to live to the age of 30. He was now 34, and he felt a deep-seated pressure to get on with his life while he still had time. So John was doing his best to understand where he was coming from, and the differences between John’s cultural experience and his were significant enough that what John thought was empathic understanding created distortion and misunderstanding

The same kind of thing can happen whenever a person with a clear cultural identity—as LGBTQ, Latina/o, female, disabled, Native American, Black or African American, millennial—interacts with a person who doesn’t share this identity. Some friends of ours with strong cultural identities have told us that they are driven up the wall by well-meaning majority people who are trying to be empathic and say things like, “I know just how you feel,” or “The same thing happened to me.” In many cases, this just flat-out can’t be true. A heterosexual person can’t know what it feels like to be bashed because you’re gay, and woman who grew up in the suburbs can’t know what it’s like to be jumped by a rival gang.

Gold and Platinum Empathy. This problem has been noticed by some people who have written about empathy and its ethical anchor, the Golden Rule. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” is a widely-accepted ethical principle that sets up the importance of, and the need for empathy. This rule is suggested in the Torah (Leviticus XIX:18), made explicit in Matthew 7:12, and is a central part of Confucius’ teachings about what he calls Kung-Shu [http://www.iep.utm.edu/goldrule/]

The potential problem is this: If you follow the Golden Rule as it’s stated, your actions toward others will be based on your own preferences about how they can best treat you. When they’re culturally different from you, the rule doesn’t require you to consider these differences. This is what John was doing with his African American friend. John had been through enough job searches to know that impatience can hurt the candidate, and, in his world, this can create problems. But John doesn’t enter the search with his friend’s life experience. The friend might learn from John’s caution that he ought to moderate his drive toward closure, but John also needs to understand the limits of his ability to be empathic.

If we bump up the empathy standard, we can get a sense of how the other person is different from us, and how their situation differs from ours, uniquely tailored to their perspective and feelings on the matter. We can then put ourselves in their place with these differences intact, added on to ours, and subtracting from ours where necessary. So we can try to occupy their perspective as them, not us, just as we’d wish them to do toward us when acting. (We wouldn’t want them to treat us as they’d wish to be treated, but as we’d wish to be treated when they took our perspective.) [Bill Puka explains this athttp://www.iep.utm.edu/goldrule/]

This way of doing empathy would follow the rule, “Treat others the way they’d wish or choose.” Some people call this “The Platinum Rule.” [http://wisdomwebsite.com/the-platinum-rule-a-golden-rule-upgrade/] It might sound like it’s almost the same as the Golden Rule, but the difference can be important for two reasons. The first is that applying the Platinum Rule forces you out of the ethnocentrism that is currently the default option for most of us. The second reason it’s important is that the other person will experience a level of confirmation and respect from you that can significantly improve everything that happens next.

The only way to practice Platinum Empathy successfully is either to know the other person very well, or to ask them how they’d like to be treated. A good prediction of their preference would have to be based on your knowledge of some track record of what they’ve liked in the past, perhaps acquired from a friend of theirs or your own experience with them as a friend. If you can’t ask, then perhaps you’re not so much treating them ethically as guessing what they’d like. Trying to put yourself in their place here would not seem like a good idea.

As Bill Puka summarizes,

Without involving others, such role-taking is a unilateral affair, whether well-intended or otherwise. It is often paternalistic, choosing someone’s best interest. The whole process is typically done by oneself, within one’s self-perspective or ego, and it can be spun as one wishes, no checks involved. Fairer and more respectful alternatives would involve not only consulting others on their actual outlooks, but including them in our decision making. “Is it OK with you if….” This approach. . .is based on a different sort of mutuality, democratizing our choices and actions so that they are multilateral. [http://www.iep.utm.edu/goldrule/]

As a practical matter, it’s pretty easy to add the kind of “check” Puka suggests to your paraphrasing of the other person. When you want to practice platinum empathy, paraphrase by restating the other’s meaning—both their main idea and some of their emotion—in your own words, and conclude your paraphrase with a perception-check. You might say, “So you’re mad enough about what happened that you think we ought to go straight to the police chief to complain, right?” Or, in another case, you might paraphrase with, “It sounds like you’re afraid that she’ll cut all of our hours if anybody complains. Does that catch what you’re saying?” Then listen, to verify that you’ve heard the other person from their point of view, not just yours.

Conclusion

The thing to remember is that the three response options go together. Only when you begin by being curious about your own cultural commitments and those of others will you be in a position to have a fruitful conversation rather than a hostile one. Only by holding your own cultural commitments loosely will you be able to understand the other person from their own point of view. And only when you practice platinum empathy will you be in a position to be genuinely curious about the difficult difference. It won’t work every time, and this three-part option is definitely worth developing into your default response in situations where you experience difficult difference.

[1] This explanation of the Cycle of Socialization draws heavily on the suggested text offered by Maurianne Adams, Lee Anne Bell, & Pat Griffin in Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2007, pp. 133-134.